Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Like many people in Elmbridge, the museum team has been spending a lot more time at home since the lockdown began.

In the absence of our usual commutes, meetings and visits around the borough, we have been immersed in the home environments we usually take for granted. Missing our regular contact with the museum collection, and surrounded by our own household objects, we decided to take a look at these in closer detail and share some of our favourites with you.

Do you have an interesting object at home and would you like to tell its story? Send your entries, along with a good quality photograph, to ebcmuseum@elmbridge.gov.uk and we will publish a selection on the Elmbridge Museum website.

I discovered this sewing machine in a charity shop in Kingston a few years ago.

I had been toying with the idea of teaching myself how to sew for a while, but I didn’t have the equipment to take on any large projects. I couldn’t believe my luck when I spotted this beautiful Singer sewing machine tucked away in the corner of the shop.

On closer inspection I discovered that it was built in the 1960s, but it was in great condition and even came with its original cover and instruction booklet. A quick test in the shop assured me that it did indeed still function, and I thought it was worth a shot!

I have used the machine for several small projects over the years, but it has really come into its own during lockdown. The long stretches at home have been the perfect opportunity to try out new skills, and I am now adept at making footstool and cushion covers. Having run out of soft furnishings to embellish, I am looking to my next challenge – making clothes!

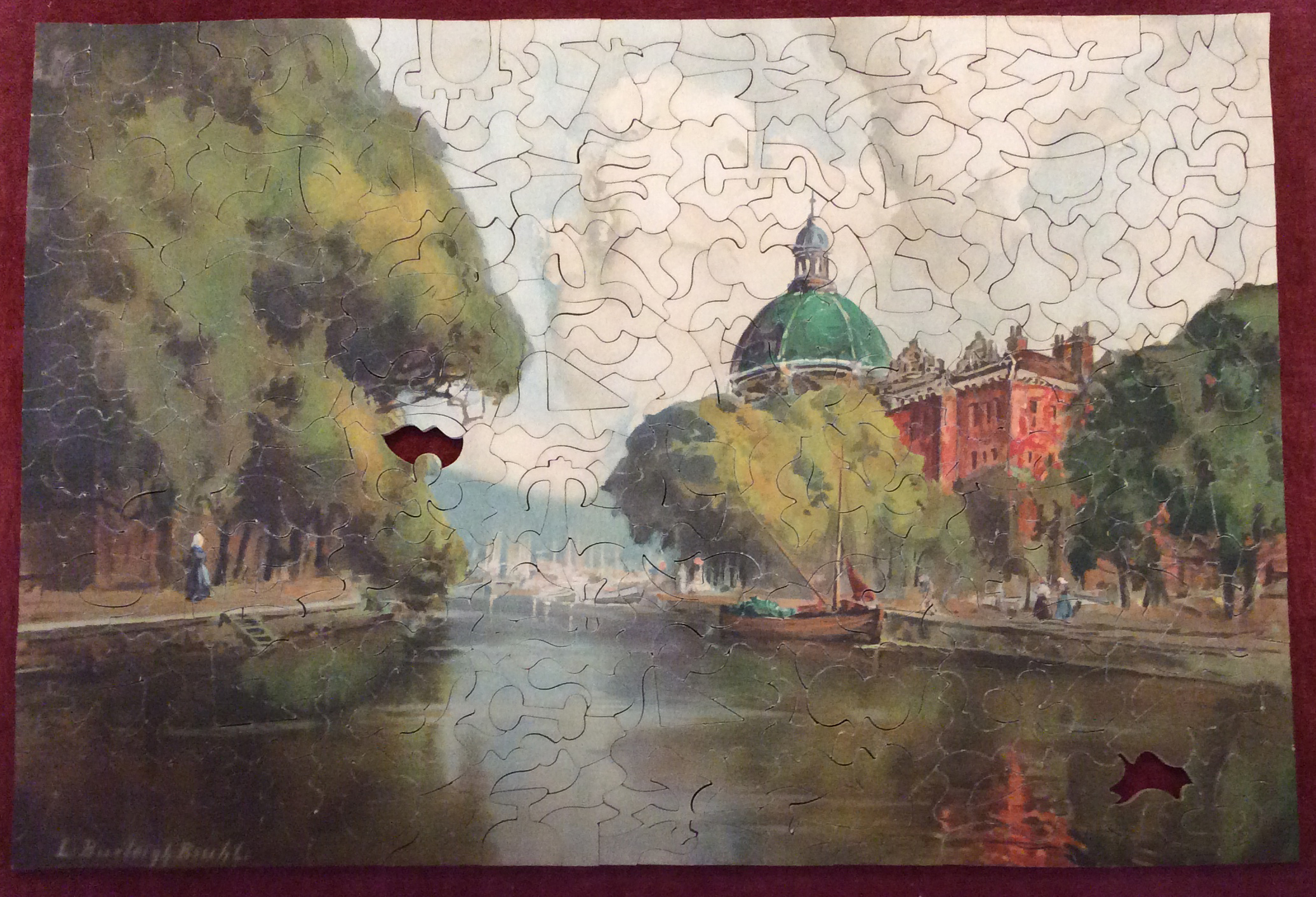

Who can resist the open invitation of a partially completed jigsaw? A quick 10 minutes can easily become an absorbing hour or two happily spent fitting pieces together. On the other hand, a particularly difficult puzzle can become a real frustration and time-waster. It is a matter of choosing carefully but who knows what really lurks within the cardboard box with the enticing picture?

With nothing seemingly left untouched in the puzzle cupboard, and family despair setting in, a decrepit box held together with garden twine was spied at the back. Black writing on the dark red box proudly proclaims ‘Incomparably the Best’ to ‘The Original British Made’ ‘Tuck’s Zag-Zaw – The Royal Picture Puzzle – A Most Fascinating Recreation – Used by Royalty, Society and the Great Public’. A forgotten treasure of wooden non-interlocking and randomly shaped pieces unearthed from the time of grand and great-grandparents.

With a seven line handwritten description in the base of the box and an unfocused 4 x 2 ½ inch 1970s photograph as the only guides to completion, progress was somewhat slow. Small clusters of pieces were placed carefully together producing recognisable features of the puzzle. Manoeuvring the clusters to make a coherent picture required great dexterity and patience.

After many hours, and as discovered written on the underneath of the box, a faded watercolour by Louis Burleigh Bruhl (1861 – 1942), entitled ‘At the Singel, Amsterdam’ was revealed, albeit sadly missing two pieces. This 400 piece zag-zaw, 19 x 13 inches, was certainly worth its 20/0 price.

With the wonders of more modern and instant technology, an I-pad image has been taken for posterity and a copy placed in the box, once again tied up with twine and returned to the puzzle cupboard for another rainy day.

Since the start of lockdown, there’s been an enormous nation-wide effort to look back on our history. I’ve enthusiastically extended this nostalgic spirit to my free time, seizing the opportunity to return to the more recent past: my school days spent in GCSE Art.

Since the start of lockdown, there’s been an enormous nation-wide effort to look back on our history. I’ve enthusiastically extended this nostalgic spirit to my free time, seizing the opportunity to return to the more recent past: my school days spent in GCSE Art.

Lockdown has provided the perfect opportunity to refocus on interests and activities that I’d normally have little time for. With this in mind, I dug out a whole range of art supplies – including a colourful spectrum of acrylic paints, oil pastels, soft pastels and watercolour pencils, along with the old sketch pad pictured above – from the Tardis which is the boot of my car, the treasure trove of art supplies having lived there since coming home from university last year.

With the words of former art teachers ringing in my ears, I’ve slowly but surely been scribbling away in this sketchpad. Sometimes the instruction to ‘let your eye tell your hand what to draw’ is not as easy to follow as it sounds, although, as pictured, I’ve so far stuck to the most golden rule – remembering to use a rainbow of colours in each piece.

I’m always amazed at the ability of art to help us to switch off, and tune into the depth and detail of our surroundings. No matter if art comes naturally or not, the therapeutic power of the activity itself can never be underestimated. Its ability to block out the outside world has a huge calming power which is especially important in lockdown, when the stresses and strains of a massively changed routine can take their toll on mental health. Although I’m a long way off from producing any artwork worthy of the museum collection, the sketchbook is certainly something I will remember to treasure in my home collection for many years to come.

My grandma was an avid collector of all sorts of weird and wonderful objects. One of her most prized collections consisted of antique breadboards, which she displayed neatly at the entrance to her flat. In her later years the collection was split amongst family members and I inherited the two pictured here. The mottoes read ‘Waste Not’ and ‘Be Thankful’, two sensible moralistic messages which chimed with the values of a resilient woman whose life was shaped by two world wars.

These breadboards have sat on my bookshelves for years without much attention paid to them, yet during the lockdown I have found myself increasingly drawn to them and wanted to find out more. For such common everyday objects, I was surprised to find a lack of resources illuminating their history. They also seem to be little represented in museum collections, including that of Elmbridge Museum.

Interestingly, breadboards do not appear to have a long history. They rose to popularity in the early 19th century following the introduction of the Corn Laws (1815-1846) which imposed tariffs on foreign wheat, pushing up the price of bread and making it an unlikely symbol of wealth and status. Rich landowners commissioned elaborately decorated boards carved with the family crest to serve their freshly baked treats.

Using a few simple clues, I discovered some information about my two inherited boards:

–The size – both of my breadboards measure 12 inches in diameter which was common in the Victorian period. Breadboards became smaller from 1900 onwards to be accommodated on plate racks.

–The lettering – appears to be in the Gothic style popularised around 1860 and later overtaken by square letting, the new height of fashion, from 1880 onwards.

–The maker – it may be impossible to know for certain who created these two examples. Breadboards were rarely stamped by their maker as it was not seen as an art-form in contrast to some other household objects such as pottery. However, it is possible they originated in Sheffield where the most prolific maker of breadboards, William Wing and his son George, were based. They seem typical of his simpler, more commercial style.

My breadboards are now back on the shelf, imbued with this new knowledge, ready to be admired for another 150 years.

There is a museum dedicated to the history of breadboards! The Antique Breadboard Museum is based in Putney and displays hundreds of examples collected over the past 40 years.

This is one of two necklaces my Great Grandma bought as a present for my Nana and Great Aunt. It has since been passed down to my Mum and then to me.

The pendant is a silver plated heart with three small hearts at the centre. The use of the heart shape to symbolise love was first seen towards the end of the middle ages. It was quickly adopted by jewelers, who found imaginative ways to incorporate symbolism into their work. Some even created acrostic jewelry in which the first letter of every gem spelt out a name or a message. In my necklace the hearts are filled with a dark resin which contrasts beautifully with the silver case.

I find it incredible how objects can provide links to the past and to people we’ve never met. Although not historically significant, this item is precious to me because of its ability to bridge gaps created by the passage of time.

During quarantine the necklace has taken on greater significance for me, as my family live too far away to visit. As well as being a link to the past, the necklace has taken on new meaning in the present day by helping me feel closer to loved ones.

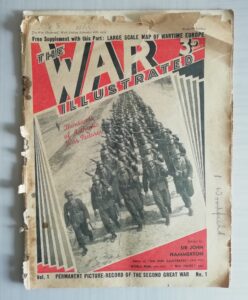

The Second World War is an event which has received much attention recently. Whether from celebrations of the 75th anniversary of its ending or comparisons (albeit tenuous) between the Blitz experience and our modern-day lockdown, there’s no doubt that it’s a part of history which many across the country have felt increasingly familiar with.

Tucked away and carefully packaged at the top of my bookshelf is where this original copy of ‘The War Illustrated’ sits. The magazines were bought religiously by my great, great uncle George as the war played out, a new edition each Wednesday. George’s dedicated collecting resulted in the accumulation of a sizeable stack, and the whole pile of crumbling papers was discovered years ago when my grandparents were clearing out his house. I managed to pilfer this copy, from September 16th, 1939, the end of the very first week of the war. It’s truly amazing to see the conflict from the perspective of those living it, and to imagine the whole range of emotions – fear, uncertainty, and anticipation among them – as they read about the unchartered waters which lay ahead. Throughout this, there is a definite sense of the importance of history: the people in 1939 looked upon the past in a desperate search for precedent, which might bring with it some guidance or comfort.

“For in a similar sense the Great War of 1939 is a continuation of that of 1914, since Nazi imperialism is an uglier beast from the same breeding ground as the one we thought we had slaughtered in 1918. “Business as Usual” was the slogan in 1914. Today “Nothing as Usual” might be its substitute. For the magical change which has come over London since the state of war was declared must be seen to be believed.” (From this original copy of The War Illustrated, 16th September 1939)

Accounts like this, written without the benefit of hindsight, are certainly rare and fascinating. A direct comparison between our present and this past may be oversimplified, but the use of history to inform and guide us has clearly remained constant.